The Economist recently ran a story airing Peak Oil concerns from "pessimists" and counters from "optimists." NPR ran a similar spot May 2.

FINANCE & ECONOMICS

The oil industry

Steady as she goes [$]

Apr 20th 2006 | BAKERSFIELD, CALIFORNIA, AND CALGARY, ALBERTA

From The Economist print edition

Why the world is not about to run out of oil

…For years a small group of geologists has been claiming that the world has started to grow short of oil, that alternatives cannot possibly replace it and that an imminent peak in production will lead to economic disaster. In recent months this view has gained wider acceptance on Wall Street and in the media. Recent books on oil have bewailed the threat. Every few weeks, it seems, “Out of Gas”, “The Empty Tank” and “The Coming Economic Collapse: How You Can Thrive When Oil Costs $200 a Barrel”, are joined by yet more gloomy titles. Oil companies, which once dismissed the depletion argument out of hand, are now part of the debate. Chevron's splashy advertisements strike an ominous tone: “It took us 125 years to use the first trillion barrels of oil. We'll use the next trillion in 30.” Jeroen van der Veer, chief executive of Royal Dutch Shell, believes “the debate has changed in the last two years from 'Can we afford oil?' to 'Is the oil there?'” But is the world really starting to run out of oil? And would hitting a global peak of production necessarily spell economic ruin? Both questions are arguable. Despite today's obsession with the idea of “peak oil”, what really matters to the world economy is not when conventional oil production peaks, but whether we have enough affordable and convenient fuel from any source to power our current fleet of cars, buses and aeroplanes. With that in mind, the global oil industry is on the verge of a dramatic transformation from a risky exploration business into a technology-intensive manufacturing business. And the product that big oil companies will soon be manufacturing, argues Shell's Mr Van der Veer, is “greener fossil fuels”.

The race is on to manufacture such fuels for blending into petrol and diesel today, thus extending the useful life of the world's remaining oil reserves. This shift in emphasis from discovery to manufacturing opens the door to firms outside the oil industry (such as America's General Electric, Britain's Virgin Fuels and South Africa's Sasol) that are keen on alternative energy. It may even result in a breakthrough that replaces oil altogether.

To see how that might happen, consider the first question: is the world really running out of oil? Colin Campbell, an Irish geologist, has been saying since the 1990s that the peak of global oil production is imminent. Kenneth Deffeyes, a respected geologist at Princeton, thought that the peak would arrive late last year.

It did not. In fact, oil production capacity might actually grow sharply over the next few years (see chart 1). Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), an energy consultancy, has scrutinised all of the oil projects now under way around the world. Though noting rising costs, the firm concludes that the world's oil-production capacity could increase by as much as 15m barrels per day (bpd) between 2005 and 2010—equivalent to almost 18% of today's output and the biggest surge in history. Since most of these projects are already budgeted and in development, there is no geological reason why this wave of supply will not become available (though politics or civil strife can always disrupt output).

| |

|

|

Peak-oil advocates remain unconvinced. A sign of depletion, they argue, is that big Western oil firms are finding it increasingly difficult to replace the oil they produce, let alone build their reserves. Art Smith of Herold, a consultancy, points to rising “finding and development” costs at the big firms, and argues that the world is consuming two to three barrels of oil for every barrel of new oil found. Michael Rodgers of PFC Energy, another consultancy, says that the peak of new discoveries was long ago. “We're living off a lottery we won 30 years ago,” he argues.

It is true that the big firms are struggling to replace reserves. But that does not mean the world is running out of oil, just that they do not have access to the vast deposits of cheap and easy oil that are left in Russia and members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). And as the great fields of the North Sea and Alaska mature, non-OPEC oil production will probably peak by 2010 or 2015. That is soon—but it says nothing of what really matters, which is the global picture.

When the United States Geological Survey (USGS) studied the matter closely, it concluded that the world had around 3 trillion barrels of recoverable conventional oil in the ground. Of that, only one-third has been produced. That, argued the USGS, puts the global peak beyond 2025. And if “unconventional” hydrocarbons such as tar sands and shale oil (which can be converted with greater effort to petrol) are included, the resource base grows dramatically—and the peak recedes much further into the future. {emphasis added}

After Ghawar

It is also true that oilmen will probably discover no more “super-giant” fields like Saudi Arabia's Ghawar (which alone produces 5m bpd). But there are even bigger resources available right under their noses. Technological breakthroughs such as multi-lateral drilling helped defy predictions of decline in Britain's North Sea that have been made since the 1980s: the region is only now peaking. Globally, the oil industry recovers only about one-third of the oil that is known to exist in any given reservoir. New technologies like 4-D seismic analysis and electromagnetic “direct detection” of hydrocarbons are lifting that “recovery rate”, and even a rise of a few percentage points would provide more oil to the market than another discovery on the scale of those in the Caspian or North Sea.

Further, just because there are no more Ghawars does not mean an end to discovery altogether. Using ever fancier technologies, the oil business is drilling in deeper waters, more difficult terrain and even in the Arctic (which, as global warming melts the polar ice cap, will perversely become the next great prize in oil). Large parts of Siberia, Iraq and Saudi Arabia have not even been explored with modern kit.

The petro-pessimists' most forceful argument is that the Persian Gulf, officially home to most of the world's oil reserves, is overrated. Matthew Simmons, an American energy investment banker, argues in his book, “Twilight in the Desert”, that Saudi Arabia's oil fields are in trouble. In recent weeks a scandal has engulfed Kuwait, too. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly (PIW), a respected industry newsletter, got hold of government documents suggesting that Kuwait might have only half of the nearly 100 billion barrels in oil reserves that it claims (Saudi Arabia claims 260 billion barrels).

Tom Wallin, publisher of PIW, warns that “the lesson from Kuwait is that the reserves figures of national governments must be viewed with caution.” But that still need not mean that a global peak is imminent. So vast are the remaining reserves, and so well distributed are today's producing areas, that a radical revision downwards—even in an OPEC country—does not mean a global peak is here.

For one thing, Kuwait's official numbers always looked dodgy. IHS Energy, an industry research outfit that constructs its reserve estimates from the bottom up rather than relying on official proclamations, had long been using a figure of 50 billion barrels for Kuwait. Ron Mobed, boss of IHS, sees no crisis today: “Even using our smaller number, Kuwait still has 50 years of production left at current rates.” As for Saudi Arabia, most independent contractors and oil majors that have first-hand knowledge of its fields are convinced that the Saudis have all the oil they claim—and that more remains to be found.

Pessimists worry that Saudi Arabia's giant fields could decline rapidly before any new supply is brought online. In Jeremy Leggett's thoughtful, but gloomy, book, “The Empty Tank”, Mr Simmons laments that “the only alternative right now is to shrink our economies.” That poses a second big question: whenever the production peak comes, will it inevitably prompt a global economic crisis?

The baleful thesis arises from concerns both that a cliff lies beyond any peak in production and that alternatives to oil will not be available. If the world oil supply peaked one day and then fell away sharply, prices would indeed rocket, shortages and panic buying would wreak havoc and a global recession would ensue. But there are good reasons to think that a global peak, whenever it comes, need not lead to a collapse in output.

For one thing, the nightmare scenario of Ghawar suddenly peaking is not as grim as it first seems. When it peaks, the whole “super-giant” will not drop from 5m bpd to zero, because it is actually a network of inter-linked fields, some old and some newer. Experts say a decline would probably be gentler and prolonged. That would allow, indeed encourage, the Saudis to develop new fields to replace lost output. Saudi Arabia's oil minister, Ali Naimi, points to an unexplored area on the Iraqi-Saudi border the size of California, and argues that such untapped resources could add 200 billion barrels to his country's tally. This contains worries of its own—Saudi Arabia's market share will grow dramatically as non-OPEC oil peaks, and with it the potential for mischief. But it helps to debunk claims of a sudden change.

The notion of a sharp global peak in production does not withstand scrutiny, either. CERA's Peter Jackson points out that the price signals that would surely foreshadow any “peak” would encourage efficiency, promote new oil discoveries and speed investments in alternatives to oil. That, he reckons, means the metaphor of a peak is misleading: “The right picture is of an undulating plateau.”

What of the notion that oil scarcity will lead to economic disaster? Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren of the Cato Institute, an American think-tank, insist the key is to avoid the price controls and monetary-policy blunders of the sort that turned the 1970s oil shocks into economic disasters. Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and the former chief economist of the IMF, thinks concerns about peak oil are greatly overblown: “The oil market is highly developed, with worldwide trading and long-dated futures going out five to seven years. As oil production slows, prices will rise up and down the futures curve, stimulating new technology and conservation. We might be running low on $20 oil, but for $60 we have adequate oil supplies for decades to come.”

The other worry of pessimists is that alternatives to oil simply cannot be brought online fast enough to compensate for oil's imminent decline. If the peak were a cliff or if it arrived soon, this would certainly be true, since alternative fuels have only a tiny global market share today (though they are quite big in markets, such as ethanol-mad Brazil, that have favourable policies). But if the peak were to come after 2020 or 2030, as the International Energy Agency and other mainstream forecasters predict, then the rising tide of alternative fuels will help transform it into a plateau and ease the transition to life after oil.

The best reason to think so comes from the radical transformation now taking place among big oil firms. The global oil industry, argues Chevron, is changing from “an exploration business to a manufacturing business”. To see what that means, consider the surprising outcome of another great motorcar race. In March, at the Sebring test track in Florida, a sleek Audi prototype R-10 became the first diesel-powered car to win an endurance race, pipping a field of petrol-powered rivals to the post. What makes this tale extraordinary is that the diesel used by the Audi was not made in the normal way, exclusively from petroleum. Instead, Shell blended conventional diesel with a super-clean and super-powerful new form of diesel made from natural gas (with the clunky name of gas-to-liquids, or GTL).

Several big GTL projects are under way in Qatar, where the North gas field is perhaps twice the size of even Ghawar when measured in terms of the energy it contains. Nigeria and others are also pursuing GTL. Since the world has far more natural gas left than oil—much of it outside the Middle East—making fuel in this way would greatly increase the world's remaining supplies of oil.

So, too, would blending petrol or diesel with ethanol and biodiesel made from agricultural crops, or with fuel made from Canada's “tar sands” or America's shale oil. Using technology invented in Nazi Germany and perfected by South Africa's Sasol when those countries were under oil embargoes, companies are now also investing furiously to convert not only natural gas but also coal into a liquid fuel. Daniel Yergin of CERA says “the very definition of oil is changing, since non-conventional oil becomes conventional over time.”

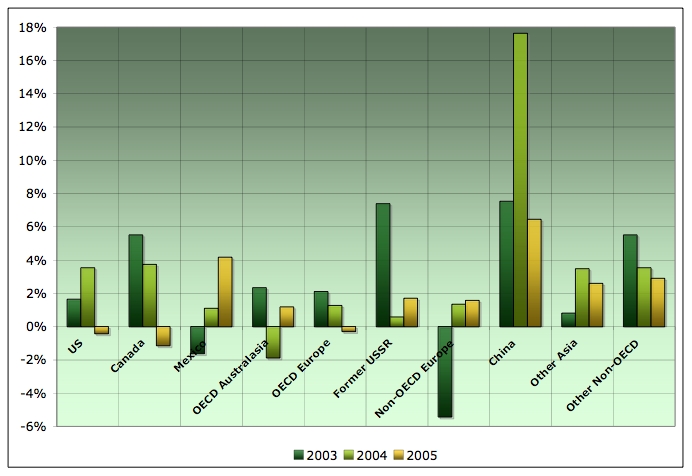

Alternative fuels will not become common overnight, as one veteran oilman acknowledges: “Given the capital-intensity of manufacturing alternatives, it's now a race between hydrocarbon depletion and making fuel.” But the recent rise in oil prices has given investors confidence. As Peter Robertson, vice-chairman of Chevron, puts it, “Price is our friend here, because it has encouraged investment in new hydrocarbons and also the alternatives.” Unless the world sees another OPEC-engineered price collapse as it did in 1985 and 1998, GTL, tar sands, ethanol and other alternatives will become more economic by the day (see chart 2).

| |

|

|

This is not to suggest that the big firms are retreating from their core business. They are pushing ahead with these investments mainly because they cannot get access to new oil in the Middle East: “We need all the molecules we can get our hands on,” says one oilman. It cannot have escaped the attention of oilmen that blending alternative fuels into petrol and diesel will conveniently reinforce oil's grip on transport. But their work contains the risk that one of the upstart fuels could yet provide a radical breakthrough that sidelines oil altogether.

If you doubt the power of technology or the potential of unconventional fuels, visit the Kern River oil field near Bakersfield, California. This super-giant field is part of a cluster that has been pumping out oil for more than 100 years. It has already produced 2 billion barrels of oil, but has perhaps as much again left. The trouble is that it contains extremely heavy oil, which is very difficult and costly to extract. After other companies despaired of the field, Chevron brought Kern back from the brink. Applying a sophisticated steam-injection process, the firm has increased its output beyond the anticipated peak. Using a great deal of automation (each engineer looks after 1,000 small wells drilled into the reservoir), the firm has transformed a process of “flying blind” into one where wells “practically monitor themselves and call when they need help”.

The good news is that this is not unique. China also has deposits of heavy oil that would benefit from such an advanced approach. America, Canada and Venezuela have deposits of heavy hydrocarbons that surpass even the Saudi oil reserves in size. The Saudis have invited Chevron to apply its steam-injection techniques to recover heavy oil in the neutral zone that the country shares with Kuwait. Mr Naimi, the oil minister, recently estimated that this new technology would lift the share of the reserve that could be recovered as useful oil from a pitiful 6% to above 40%.

All this explains why, in the words of Exxon Mobil, the oil production peak is unlikely “for decades to come”. Governments may decide to shift away from petroleum because of its nasty geopolitics or its contribution to global warming. But it is wrong to imagine the world's addiction to oil will end soon, as a result of genuine scarcity. As Western oil companies seek to cope with being locked out of the Middle East, the new era of manufactured fuel will further delay the onset of peak production. The irony would be if manufactured fuel also did something far more dramatic—if it served as a bridge to whatever comes beyond the nexus of petrol and the internal combustion engine that for a century has held the world in its grip.

The European Commission admitted Monday that member states had given companies far too generous targets for greenhouse gas emissions last year, raising questions about the Continent's ability to meet its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol and triggering chaos in Europe's embryonic market in trading emissions credits.

The European Commission admitted Monday that member states had given companies far too generous targets for greenhouse gas emissions last year, raising questions about the Continent's ability to meet its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol and triggering chaos in Europe's embryonic market in trading emissions credits.